When you have any trait or condition, it’s natural to wonder where you got it from, and if your children might have it too. ADHD is no exception to this, although the stream of thought that fuels that question is very individual.

Some may wonder if their loveable family quirks are really familial ADHD. Others are horrified at the thought of their children potentially experiencing the same difficulties and stigma as their parents.

I recently went through genetic testing with 23andme (using a kit like this). This wasn’t for very exciting reasons – I’ve been having tests for coeliac disease, and wanted to see if I had the associated genes.

However, their test can tell you about a lot of traits you may inherit – including some relevant to ADHD.

So is ADHD inheritable?

Probably.

Through twin and adoption studies, we know that it is common for ADHD to run in families. Although the prevalence of ADHD in children worldwide is estimated at 5%, estimates of the condition’s heritability are usually around 80%. This means that on a population level, the chance of developing ADHD is vastly more influenced by our genetics, than by factors in our environment. Environmental factors can be anything from exposure to smoking, to injuries to the frontal lobe of the brain.

In general, if you have ADHD, your child has at least a 50% chance of also having ADHD. In my family, both my brother and I have been diagnosed with ADHD (but as the older sibling, I have to make it clear that I was diagnosed first and he simply copied me…! 😉). Although my parents have never been formally assessed, I would bet a lot of money that they also have ADHD.

In fact, when I told them I was being assessed for ADHD, my parents said that my symptoms couldn’t be due to an undiagnosed neurodevelopmental condition, because they had the same traits at my age so therefore I was perfectly normal.

Does this sound familiar to anyone?

I can certainly see common traits between myself and my parents.

Although my dad is now retired, his former colleagues were very used to his idiosyncrasies – one described working with him as “like trying to herd sheep around a roundabout”. He can’t concentrate on the TV unless he’s also using his iPad – if you forbid him from multitasking like this, he’ll fall asleep.

My mum, meanwhile, is known for her ‘Friday night ideas’ – brilliant flights of creative thought, after dinner is finished, that often lead to an impulsive decision or purchase. My personal favourites include a Cocker Spaniel, an exercise bike she’s never used, painting the whole kitchen and a single wall in every room of the house the same shade of green, and two rescue kittens. For those who know me, this one paragraph describing my lovely parents is all the evidence anyone needs to prove that I’m their child!

Although their ADHD-ness is not diagnosed, my Mum often wonders if my brother and I inherited it from her, or my dad, or both of them – or if it’s a result of something we were exposed to as children. Interestingly, my 23andme results supported the theory that I have inherited my neurodivergence from at least one of my parents.

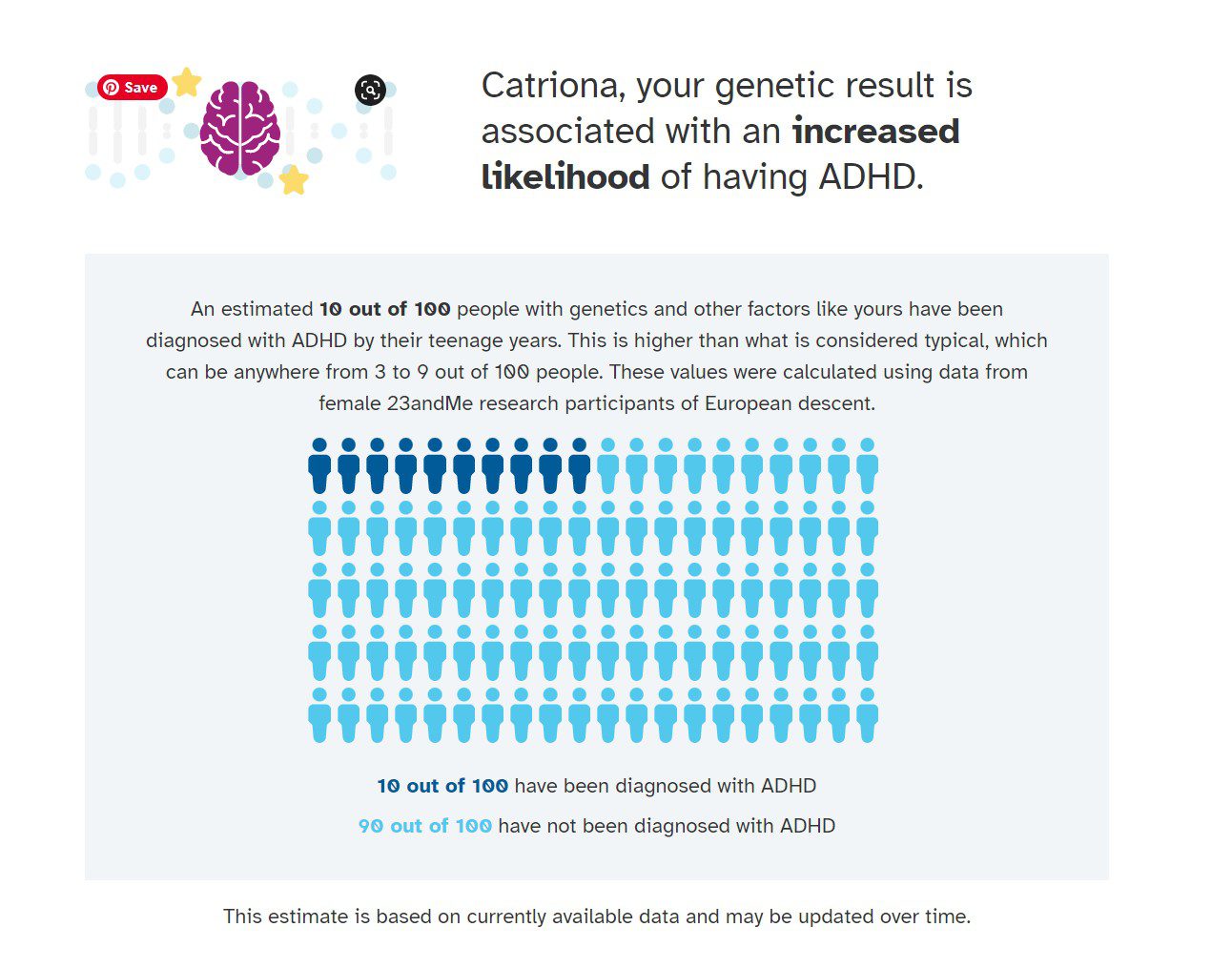

I was told that out of 100 people with genetics like mine, 10 are estimated to have been diagnosed with ADHD by their teen years. This was considered as an increased likelihood, which surprised me. Typical likelihood is anywhere between 3 and 9 out of 100 people, which seems quite borderline.

However, although I could think this test was quite accurate as I do indeed have ADHD, I was still curious about its validity on a statistical level.

The predicted likelihood is based on surveying users of 23andme, and then seeing which traits are common in those with certain genes. People with ADHD could be less likely to do a 23andme test, so less of the sample have ADHD – this could skew the results to suggest that less people with a gene have ADHD.

Additionally, you may be familiar with the challenges in accessing a diagnosis of ADHD. Their survey only asks about a confirmed diagnosis, so those with suspected ADHD, or those diagnosed after their test, will not be included in the figures. As we don’t know the specific genetic basis of ADHD, the test also can’t check for every possible genetic factor.

However, the statistical model used by 23andme has looked at over 15,000 genetic markers, and they state that taking the potential error margin into account, there is a 99% chance that my ‘increased likelihood’ result is accurate.

All in all, the real likelihood could be different, and of course, 23andme won’t be taking environmental factors into account.

So how can we investigate what exactly makes ADHD so inheritable?

We need to look at the genetics.

Initially, geneticists looked at the links between ADHD and particular segments of DNA. Scientific development has allowed us to also look at our DNA on a molecular level, and nowadays we can look at the whole genome.

However, there is a lot of disagreement about whether there are specific sections of our DNA that are associated with developing ADHD, and if so, which ones. Some conditions and traits can be narrowed down to a specific code that causes them, but so far, we haven’t found the exact genetic home of ADHD.

Some studies’ findings have overlapped, and scientists now believe that there are a range of locations in our genome that could plausibly be connected to ADHD.

The neurotransmitter dopamine is known to be implicated in the mechanism of ADHD, and some of our symptoms. Studies have shown that ADHD is often associated with low levels of the neurotransmitter, dopamine, or problems with how it works.

My favourite analogy for this is:

Your brain is a car.

Dopamine is petrol.

If you have ADHD, one theory is that your car doesn’t have enough petrol to run like the other cars.

Or, your car has plenty of petrol – but the engine will only respond to diesel!

DUSP6 is a gene that affects the levels of dopamine in our synapses (the junctions between our neurons), and is just one of the many genes that have shown an association with ADHD. We have also looked at genes involved in our response to drugs used in the treatment of ADHD, such as amphetamines, to try and find a genetic explanation for why these medications work. If we can’t find a specific ‘ADHD gene’, we might be able to find genes that explain the individual errors, or ‘miswiring’, that individually add up to result in the symptoms and traits we know as ADHD.

However, most of the research is yet to show statistical significance – meaning that although we have some evidence for the role of certain genes, there just isn’t quite enough to confidently support the link.

Other studies have reported that the genes thought to be associated with ADHD are often linked to those associated with known ADHD comorbidities, such as conduct disorder depression. Some have said that the relatives of people with ADHD have a greater risk of mental illness, most notably schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

We can also look at the heritability of ADHD without knowing the exact gene ‘to blame’.

We know, for example, that children with a low birth weight, those who are born premature, and children whose mothers had problems in pregnancy, have a higher risk of ADHD compared to children without these factors.

Genetically Caffeinated

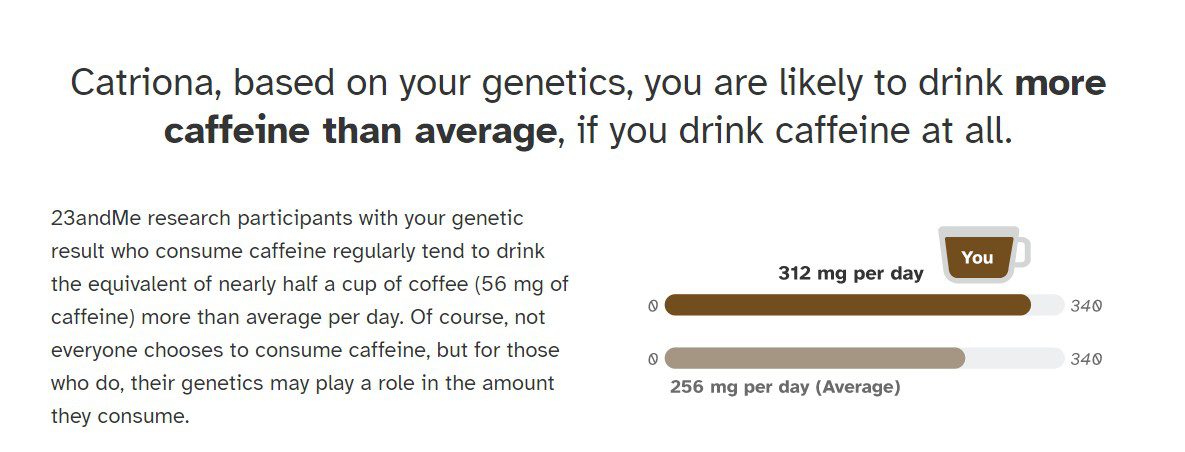

Interestingly, 23andme also reports that my genetics are associated with drinking more caffeine than average.

People with ADHD often self-medicate with caffeine, as it can help us to focus due to having a similar effect in the brain as medications like methylphenidate (e.g. Ritalin and Concerta) – you can read more about caffeine and ADHD in my post here.

From the information 23andme has given alongside my results, they have based this likelihood of increased caffeine consumption on having genes that often give you an increased ability to break down caffeine. This should give you a better tolerance to it, so theoretically you are likely to drink more.

I’m not sure how we can conclude that handling the effects of caffeine positively means you’re likely to drink more of it, but anyone who has seen the volume of Pepsi Max I consume in a week would not be surprised by this result…

So can you inherit ADHD? Is it genetic?

Overall, the research to date shows that ADHD is mostly genetic, but there isn’t one single ‘ADHD gene’.

It is likely that a lot of genes influence your chance of developing ADHD, but the environment you grow up in will also play a small part.

Some studies have reported strong evidence to support the theory that everyone carries genetic variants for ADHD, but the variants contribute additively to your liability.

To paraphrase:

The more genes you carry, the more likely you are to develop ADHD.

This would also mean that clinically-defined ADHD is just one end of a spectrum, of a trait that varies continuously in the population.

This would fit very nicely into a neurodiversity perspective of ADHD, where the condition is simply one extreme of the natural spectrum of variation in how our brains work.

Hi!

I loved that your page exists, super helpful. I have been reviewing my Nan’s 23andme results as I bought her the kit for her birthday and it came back typical likelihood 6 out of 100 people with her genes have it. Myself and my cousin have been diagnosed with ADHD and my late mum and late aunt of the cousin were rife with ADHD traits, to the extent my Nan (their mum) has always spoke about how hyperactive that were. I also see the traits in the rest of my large family and out of everyone, my Nan the most, who has done the 23andme test. I wondered what your thoughts were on what ‘typical likelihood’ means? What is the different between typical likelihood Vs increased likelihood when it comes to ADHD? I suppose as an example, let’s say we compared both your results, you being increased likelihood and let’s say my Nan at 80 was diagnosed officially with ADHD but here says typical likelihood, what do the results then mean, if you both have ADHD but your likelihood is different? This has baffled me. Hope to hear back, many thanks!